Summer 2019

Welcome from EUS-AAEM

The Emergency Ultrasound Section of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine (EUS-AAEM) is founded to foster the professional development of its members and to educate them regarding point of care ultrasound. This group will serve as a venue for collaboration among medical students, residents and practitioners who are interested in point of care ultrasound. The purpose of our group is to augment the knowledge and expertise of all emergency medicine specialists and to advocate for patient safety and quality care by endorsing bedside ultrasound. Membership is not limited to fellowship trained physicians. All emergency medicine practitioners passionate about ultrasound are welcome to join and participate.

We are proud to publish our e-newsletter with original contributions from many of our members. We encourage all members to submit for future additions. Topics include but are not limited to educational, community focus, interesting cases, resident and student section, and adventures abroad.

For more information visit us online at: www.aaem.org/EUS

In this Issue:

-

President's Message

-

Ultrasound Building Blocks: Ultrasound Guided Ankle Arthrocentesis

-

Resident Section: Updates on the Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship Match

-

Ultrasound Highlights

-

Mental Break- Clinical Image: Not so FAST - The RUQ

-

Focus on Education: POCUS is the Future of Prehospital Resuscitation

-

Administrative Corner: Reimbursement and Coding of Point of Care Ultrasound: Bringing Your Ultrasound Program to the Next Level

-

Ultrasound Saves: Chest Pain Conundrum - Bedside Ultrasound Diagnoses a Complex Case of Undifferentiated Chest Pain

-

From Journal to Practice: POCUS and Your Next Cardiac Arrest: A Case Scenario Application of the Lalande et al. Review Article

-

Letter to the Editors

-

Get Involved

President's Message

Greetings EUS-AAEM Section Members,

I’m excited to be taking over as EUS-AAEM section President for 2019-2020. Building upon the great work that Drs. Ryan Gibbon and Mark Magee have done leading our section, I hope to continue to provide value for our over 800 members and establish ourselves as a distinct and important part of the emergency ultrasound community. Some of the items we’ll be working on this year are:

- Regional Ultrasound Courses: We plan to roll out our first EUS-AAEM US course for various AAEM chapter divisions later this year or next to provide more access to US education.

- Skill Verification Program (SVP): For EM docs no longer in training, we are developing the SVP to help community providers, who do not have access to a fully developed US program, achieve additional ultrasound privileges at their institution by providing a pathway to verify US skills during our US educational events.

- Medical Student-Level, Resident-Level, and Fellow-Level Training Opportunities: We are working on different avenues for you to gain additional US skills that you may not have access to locally. Look for upcoming opportunities at regional US courses or the upcoming AAEM20 Scientific Assembly on April 19-23, 2020 in Phoenix, AZ.

- The Definitive US Resource: Have you noticed that there is a ton of US educational content out there? It is hard to tell what the best content is. We are exploring the development of a dynamic expert- and user-curated EUS-AAEM website helping you find the best website/video on US topic “XYZ.”

There are a lot of ways to get involved with EUS-AAEM this year, please email me (business@thechinfamily.com) if you’d like more information and have not already reached out to me. If you have already reached out to us, our committee chairs will likely be reaching out to you in the coming months. If you have any other suggestions on what you’d like YOUR section to do for YOU, please let us know.

Sincerely,

Eric Chin, MD MBA FAAEM

EUS-AAEM President 2019-2020

Ultrasound Building Blocks

Ultrasound Guided Ankle Arthrocentesis

Melissa Myers, MD and Kristine Jeffers, MD

Case

A 55 year old male presented to a community emergency department (ED) complaining of ankle swelling. He reported a history of gout, although he had never had pain in the ankle, and stated that he had had a fever earlier that day. He was afebrile with normal vital signs in the ED. The nurse practitioner who originally evaluated the patient was concerned for septic arthritis and turned the case over to the attending emergency medicine physician, who planned an ankle arthrocentesis. However, the physician had some concerns performing this fairly uncommon procedure and considered using ultrasound guidance to improve her chances of success.

Introduction

Arthrocentesis is a common and essential ED procedure. Emergency physicians frequently perform arthrocentesis of large joints such as the knee, but may feel less confident when approaching arthrocentesis of the ankle, elbow or wrist. Many emergency physicians are familiar with ultrasound guidance for arthrocentesis of the knee and it is relatively straightforward to expand the use of this technique to other joints such as the tibiotalar joint in the ankle.1 Ultrasound can be useful both before and during the procedure, to confirm the presence of an effusion and for real-time needle guidance during the procedure.

Ultrasound has been shown to be superior to physical exam in the diagnosis of knee effusion. A few minutes performing an ultrasound prior to initiation of the procedure may save a significant amount of time and frustration if no significant joint effusion is present. In one study involving examination of 44 knee joints, ultrasound detected 27 knee effusions compared to 16 by physical exam.2 A second study of 54 emergency department patients showed that ultrasound changed the management in a significant number of patients with suspected joint effusions. 54 patients with joint pain, erythema or swelling were enrolled and it was found that ultrasound changed the management in 35 of these patients. 19 patients did not undergo a planned arthrocentesis after ultrasound. More importantly, 8 patients underwent a previously unplanned arthrocentesis and 4 of these were diagnosed with septic arthritis.3 Furthermore, ultrasound decreases time to diagnosis as it can be performed rapidly at the bedside instead of waiting for results from a plain film or other imaging.

Ultrasound guided ankle arthrocentesis is well within the capabilities of any emergency physician who is familiar with musculoskeletal ultrasound. Ultrasound guidance is an extremely useful technique for ankle arthrocentesis, either as a primary approach or as an adjunct if a standard landmark approach has failed. Ultrasound guided arthrocentesis of the tibiotalar joint has been described in the literature as early as 1994 and is described in commonly available emergency medicine textbooks.5 Emergency medicine residents who underwent a 30 minute training were 88% sensitive and 90% specific for diagnosis of ankle effusion in a cadaver mode and felt more confident in performing the procedure under ultrasound guidance. However, there was no statistical difference between ultrasound guidance and landmark guidance in number of attempts or time needed to perform the procedure.6

Procedure

- Establish a sterile site. Use a sterile probe cover and sterile ultrasound gel.

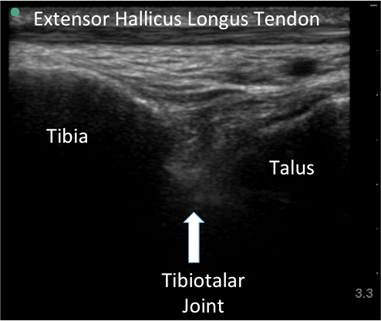

- Place a linear (high frequency) probe on the anterior aspect of the ankle with the indicator oriented towards the patient’s head. You will see the tibiotalar joint, with the distal tibia on the same side of the screen as the probe indicator. If there is an effusion, it will be as an anechoic space between the tibia and the talus. Identify any tendons or vascular structures in view and orient the probe so that the needle path will not injure these structures.

- The needle can be inserted medially on the probe or from the inferior aspect. Use the approach which will most easily allow access to the visualized joint effusion while avoiding other structures. Advance the needle while withdrawing until fluid is aspirated.

Figure 1. Linear probe positioned to visualize the tibiotalar joint

Figure 2. Visualization of the tibiotalar joint

Figure 3. Medial and Inferior Approaches to the joint

Case Conclusion

An arthrocentesis was performed using ultrasound guidance. The synovial fluid was noted to have urate acid crystals with a WBC count of less than 50,000 and a negative gram stain. The patient was discharged with treatment for gout.

References

- Tirado, A., Wu, T., Noble, V. E., Huang, C., Lewiss, R. E., Martin, J. A., ... & Sivitz, A. (2013). Ultrasound-guided procedures in the emergency department—diagnostic and therapeutic asset. Emergency Medicine Clinics, 31(1), 117-149.

- Kane, D., Balint, P. V., & Sturrock, R. D. (2003). Ultrasonography is superior to clinical examination in the detection and localization of knee joint effusion in rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology, 30(5), 966-971.

- Adhikari, S., & Blaivas, M. (2010). Utility of bedside sonography to distinguish soft tissue abnormalities from joint effusions in the emergency department. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 29(4), 519-526.

- Roy, S., Dewitz, A., & Paul, I. (1999). Ultrasound-assisted ankle arthrocentesis. The American journal of emergency medicine, 17(3), 300-301.

- Reichman, E. F. (2018). Reichman's Emergency Medicine Procedures. McGraw Hill Professional.

- Berona, K., Abdi, A., Menchine, M., Mailhot, T., Kang, T., Seif, D., & Chilstrom, M. (2017). Success of ultrasound-guided versus landmark-guided arthrocentesis of hip, ankle, and wrist in a cadaver model. The American journal of emergency medicine, 35(2), 240-244.

Resident Section

Updates on the Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship Match

Eric Chin, MD MBA FAAEM - EUS-AAEM President 2019-2020

Neha Bhatnagar, MD - EUS-AAEM RSA Representative and Aspiring Ultrasound Fellow

Building on the success of last year’s national match process, the more than 100 member programs of the Society of Clinical Ultrasound Fellowships (SCUF) will again be using the National Residency Match Program (NRMP) to pair prospective emergency ultrasound fellowship candidates with available fellowship openings.

Now is a great time to consider applying for an ultrasound fellowship as 87% of the 2018 applicants matched with their first choice, and many slots remained available. For those who missed it, you can read our 2018 article on the Emergency Ultrasound Match here.

The application process remains essentially unchanged from last year, but below are the new 2019 Deadlines to keep in mind:

- August 21 at 12:00pm EST - EM Subspecialty Match opens.

- September 18 at 12:00pm EST - Ranking opens.

- November 6 at 9:00pm EST - Rank Order List (ROL) Deadline for Submission and Certification.

- November 20 at 12:00pm EST - Match Day! Offers will be sent via email.

At the SCUF19 Conference, Dr. Jeremy Boyd discussed the following statistics on the first Match which were quite interesting:

- Number of applicants: 100

- Number of fellowship programs: 116

- Number of fellowship positions (some programs have multiple positions): 194

- Number of applicants who got their first choice: 87

- Number of applicants who got their second choice: 6

- Number of applicants who got their third choice or more: 2

- Number of applicants that went unmatched: 5

So if the numbers are similar this year, then applicants can look forward to generally favorable odds!

When submitting the application, all of the following are things to consider including: education, research/publications/presentations, leadership positions, extracurricular, ultrasound experiences/logs, procedure/clinical logs, Step 3 score, In-Training Exam scores, other work experience, and service/volunteer experience.

However, what is most important is knowing why you are seeking an ultrasound fellowship and being able to communicate that clearly to the directors.

When it comes to the Letters of Recommendation, consider asking your program director, ultrasound director/faculty, or other faculty mentor who knows you well. It is key though, no matter who you ask, to be sure the letter writer feels able to write a strongly favorable letter advocating for you.

Factors to consider when choosing a fellowship are similar to what you would look for in any job: the people and workplace culture, location, institution, practice model (academic, community, county, independent group, hospital or corporate employee), compensation/benefits, census/acuity, moonlighting structure, etc.

Some questions are more specific to ultrasound fellowship: the director’s and the program’s mission, how the fellowship is organized in regards to clinical shifts vs scanning shifts vs other responsibilities (i.e. admin, QA, education, research), what their previous fellows went on to do after fellowship (if applicable), what machines/probes/image storage they use, the billing and QA structure, what projects they have going and what they would like to get started, how many faculty besides the director are involved with fellows and how often do they meet with you, what does the resident ultrasound experience entail (if applicable), and more. Much of this information is available in the programs’ profiles on the SCUF website: http://www.eusfellowships.com.

Just like with any job interview, applicants should be ready to answer questions about their reasons for seeking fellowship, what they hope to accomplish, and why they are interested in that specific program.

At the end of the day, most fellowship directors are simply looking for applicants who are motivated individuals interested in mastering an additional skill set. So if that sounds like you, consider applying for Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship starting this August!

Resources List:

- POCUS Report article on the Emergency Ultrasound Match

- EUS Fellowships and SCUF Website

- NRMP EM Fellowship Match Deadlines

- NRMP Match Fees

- AAEM’s Emergency Ultrasound Section (EUS)

- ACEP’s Ultrasound Section

- SAEM’s Academy of Emergency Ultrasound (AEUS)

- EMRA Ultrasound Section including the Fellowship Guide Chapter for Ultrasound

- ALiEM’s EM Fellowship Match Advice

- American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM)

Ultrasound Highlights

Five Tips to Up Your POCUS Game - Jacob Avila, MD RDMS

Learn some tips and tricks to transition from an ultrasound novice to a "sono- star."

Login to your AAEM account to watch this video.

Goal-Directed Echocardiography – Three Simple Views that will Change Your Practice - John Greenwood, MD FAAEM

Traditional emergency department (ED) echocardiography is intended to estimate left ventricular function and diagnose pericardial tamponade. Adding three simple measurements to the standard views already being obtained can dramatically impact clinical decisions and management strategies for the unstable patient.

Login to your AAEM account to watch this video.

Mental Break

Clinical Image: Not so FAST - The RUQ

Eric Schwartz, MD and Neeraj Gupta, MD FAAEM

Einstein Healthcare Network

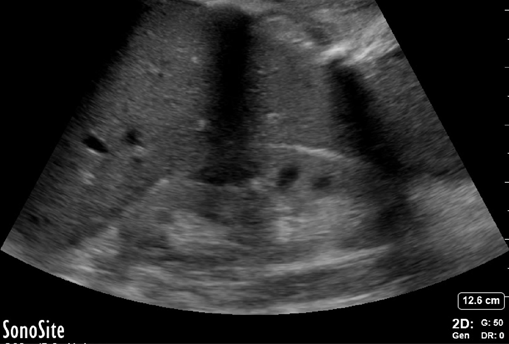

HPI: 35 yo woman with history of ESRD on HD presents for increasing abdominal distension for several weeks. On exam, the abdomen is obese and distended. There is diffuse tenderness without rebound or guarding. A FAST exam was performed to assess for the presence of intra-abdominal fluid.

Figure 1: Morrison’s pouch

Figure 2: Liver tip

Take Home Point

The above images demonstrate the importance of obtaining views of the entire right upper quadrant when assessing for free fluid. Although Morrison’s pouch is the most common place for fluid to accumulate in the RUQ, the entire area must be scanned to increase sensitivity. When scanning the RUQ, it is important to assess for the presence of fluid above and below the diaphragm, at the hepato-renal interface (Morrison’s pouch), the liver tip, and the superior and inferior poles of the kidney. The findings in this case were secondary to ascites; however, this concept is generalizable to FAST exams performed during traumas.

Focus on Education

POCUS is the Future of Prehospital Resuscitation

Andrew Merelman, BS NRP FP-C

Critical Care Paramedic, First-Year Medical Student

Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Parker, Colorado

Paramedics are used to making critical decisions with minimal diagnostic information. Aside from basic physical exam skills, the only diagnostics widely available are vital signs, electrocardiography, and glucometry. But paramedics are tasked with performing advanced procedures such as intubation and cardiac resuscitation with these basic diagnostic and assessment tools. Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) can provide substantial clinical information when deciding to initiate and maintain these treatments. Hospital providers are already using POCUS to manage critically ill patients. Many of the emergency department applications of POCUS can be translated to prehospital care. Until recently the limiting factor has been device portability. There are now an assortment of available devices that can be easily used in the prehospital setting which deliver quality images.

There are a number of POCUS modalities commonly used in the emergency department which may be useful in the prehospital environment.1 It is common for prehospital providers to encounter patients with acute dyspnea. Distinguishing between reactive airway disease and pulmonary edema can be difficult if the patient has a complicated medical history or unusual presentation. Auscultation is not always reliable for these conditions whereas POCUS can identify them with a high sensitivity and specificity.2,3 POCUS can provide definitive information and allow for targeted prehospital treatment. Additionally, diagnosis of pneumothorax can be extremely challenging when using only auscultation and POCUS can confirm the diagnosis before needle decompression or thoracostomy are performed.

POCUS could be useful in the pre-hospital management of the patient in profound shock. The Rapid Ultrasound in Shock (RUSH) exam can provide valuable information about the etiology of shock so that appropriate treatment can be rendered.4,5 The RUSH exam focuses on three areas: the pump (heart), the tank (venous system), and the pipes (arterial system). By scanning these areas paramedics can assess for cardiac function, aortic disasters, and volume status. They can also determine the presence or absence of pericardial tamponade, pleural effusion, and pulmonary edema. Use of POCUS in this situation can help to determine the need for intravenous fluids, vasopressors or immediate transport for further care.

The role of ultrasound in cardiac arrest has expanded in the emergency department and can also be applied in the field. The limited echocardiogram can provide an assessment of cardiac function and the ability to identify underlying causes, which may help providers to make transport decisions. The FEEL trial demonstrated that ultrasound can be especially valuable in the prehospital management of pulseless electrical activity (PEA)6 by evaluating for the presence or absence of cardiac activity. If cardiac activity is present, this suggests a reversible cause such as severe hypovolemia or pulmonary embolus. The identification of a reversible cause can signal paramedics to deliver a specific therapy such as fluid resuscitations, electrolyte administration, vasopressor administration, or initiation of rapid transport for definitive treatment.

These are only a few of the applications for POCUS in the prehospital setting. Ultrasound provides paramedics with diagnostic information in a non-invasive manner and may improve their ability to deliver direct and accurate treatment. Prehospital ultrasound has been shown to be useful in as many as one of every six cases in an environment with a large number of trauma patients.8 In one preliminary study, paramedics demonstrated the ability to perform clinically useful ultrasounds in the field.9 The implementation of POCUS seems to be the next logical step in advancing the level of care provided in the prehospital setting.

References

- Bøtker MT, Jacobsen L, Rudolph SS, Knudsen L. The role of point of care ultrasound in prehospital critical care: a systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2018;26(1):51. doi:10.1186/s13049-018-0518-x

- Ebrahimi A, Yousefifard M, Mohammad Kazemi H, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Chest Ultrasonography versus Chest Radiography for Identification of Pneumothorax: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Tanaffos. 2014;13(4):29-40. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25852759. Accessed November 8, 2018.

- Zanatta M, Benato P, De Battisti S, Pirozzi C, Ippolito R, Cianci V. Pre-hospital lung ultrasound for cardiac heart failure and COPD: is it worthwhile? Crit Ultrasound J. 2018;10(1):22. doi:10.1186/s13089-018-0104-5

- Ghane MR, Gharib MH, Ebrahimi A, et al. Accuracy of Rapid Ultrasound in Shock (RUSH) Exam for Diagnosis of Shock in Critically Ill Patients. Trauma Mon. 2015;20(1):e20095. doi:10.5812/traumamon.20095

- Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, Mandavia D. The RUSH Exam: Rapid Ultrasound in SHock in the Evaluation of the Critically lll. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28(1):29-56. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2009.09.010

- Breitkreutz R, Price S, Steiger H V., et al. Focused echocardiographic evaluation in life support and peri-resuscitation of emergency patients: A prospective trial. Resuscitation. 2010;81(11):1527-1533. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.07.013

- Blyth L, Atkinson P, Gadd K, Lang E. Bedside Focused Echocardiography as Predictor of Survival in Cardiac Arrest Patients: A Systematic Review. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(10):1119-1126. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01456.x

- Hoyer HX, Vogl S, Schiemann U, Haug A, Stolpe E, Michalski T. Prehospital ultrasound in emergency medicine: incidence, feasibility, indications and diagnoses. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):254-259. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328336ae9e

- Heegaard W, Hildebrandt D, Spear D, Chason K, Nelson B, Ho J. Prehospital Ultrasound by Paramedics: Results of Field Trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(6):624-630. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00755.x

Administrative Corner

Reimbursement and Coding of Point of Care Ultrasound: Bringing Your Ultrasound Program to the Next Level

Jason Adler, MD FAAEM and Alexis Salerno, MD

Introduction

The use of point of care ultrasound in the emergency department has increased significantly over the past 5-10 years. As our specialty evolves, so do the tools in our diagnostic toolbox. The use of ultrasound is more than an extension of our stethoscope; ultrasound is a diagnostic study that supports the rapid assimilation of data and diagnoses. Many of these procedures are also reimbursable.

Similar to other services provided in the emergency department and medicine in general, the process of reimbursement begins with coding the medical record. Coders use Current Procedural Terminology, CPT®, which is maintained by the American Medical Association, to apply an accurate code for the service rendered. Codes are then processed for reimbursement depending on their value. Each year, the codes are updated by the AMA CPT Advisory Committee, with representation from each specialty society.

I interviewed Dr. Jason Adler to find out more about emergency department coding and reimbursement of ultrasound. Dr. Adler is a board certified emergency physician and subject matter expert in coding and reimbursement. After spending the early part of his career at an independent democratic group, he now works clinically as Clinical Assistant Professor at the University Of Maryland School Of Medicine. Dr. Adler is also the Vice President of Practice Improvement at Brault, an acute care coding, revenue cycle, and practice management firm.

Question 1: Which ultrasound examinations can emergency physicians be reimbursed for?

Board certified emergency physicians are frequently using ultrasound in their clinical practice. Our specialty training includes many ultrasound exams which when performed, are considered a separately billable procedure.

One of the most common examples of ultrasound done by the EP is for trauma patients. The FAST exam is used to rapidly evaluate a trauma patient for bleeding around the heart or in the abdomen. There is no single CPT® for this study; it is coded as a combination of a limited transthoracic echo (93308, -26) and limited abdomen (76705, -26). You can also perform an ultrasound of the chest (76604, -26) to evaluate for a pneumothorax.

For the medical patient, the chest ultrasound (76604, -26) can evaluate a patient for pulmonary edema. A limited abdominal ultrasound (76705, -26) can be done to look for gallbladder disease and a limited retroperitoneal study (76775, -26) to evaluate for aortic aneurysm or renal disease. In other cases, for example, a pregnant patient with vaginal bleeding, a transabdominal (76815, -26) can be used to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy, a time sensitive and critical diagnosis.

Ultrasound exams are also being used to improve the safety and accuracy of critical procedures. These exams include central line placement (76937, -26) using a dynamic technique (where the ultrasound is used to identify the vessel through the needle entry). Ultrasound can also be used as guidance for needle placement, for example, lumbar puncture (76942, -26), thoracentesis (32555, -26), and paracentesis (49083, -26).

Question 2: What is involved in setting up an ultrasound program which captures reimbursement?

A few steps are recommended to start an ultrasound program and appropriately capture reimbursement. The clinician should be credentialed by the hospital to perform the procedure, but it’s not necessarily required for reimbursement purposes by CPT®. You need to have a mechanism in place to retain and store images. Then, you would need to discuss policies and procedures with your coding vendor and have a process in place to document why you are performing the study, what you find, and demonstrate the medical necessity of the exam.

Question 3: What is the difference between professional and technical components of ultrasound billing?

The professional component of the ultrasound exam is performed by the clinician and covers the supervision, interpretation and documentation of the results. When only reporting the professional component, a -26 modifier is added to the procedure code. The technical component is typically captured by the facility with a -TC modifier, and includes the cost of equipment, supplies, clinical staff, practice and malpractice expenses.

And although we are seeing some emergency departments purchasing machines for dedicated use in the ED, and individual clinicians purchasing portable devices, it is generally not recommended to report the technical fee in this setting.

Question 4: Can you explain the difference between a limited and complete ultrasound examination from a coding perspective?

A complete ultrasound exam, per CPT®, is intended to visualize and diagnostically evaluate all the major structures within the anatomic description. There are specifications related to the area studied, and type of imaging (e.g. B-mode vs Doppler). In contrast to a complete exam, a limited ultrasound exam, per CPT®, is one in which less than the required elements are performed and documented. Therefore, most emergency department ultrasounds are considered limited exams- because in this setting, exams are focused to only a particular diagnostic question.

The abdominal ultrasound exam is a frequently cited example to describe the differences between the complete exam (76700) and the limited exam (76705). The complete abdominal exam, often performed by a radiologist, would include images and comments on the liver, gallbladder, common bile duct, pancreas, spleen, kidneys, the upper abdominal aorta, and inferior vena cava, with specific pertinent positive and negative findings for each or the reason why the exam element could not be visualized. In contrast, a limited abdominal ultrasound, (76705), may be performed to look at one single organ, or quadrant such as the gallbladder or spleen to evaluate for acute cholecystitis or splenic injury. Generally, best practice for documenting the written report includes 2-3 interpretive comments for each exam element.

A common exception to the complete or limited exam is a transvaginal ultrasound for the pregnant patient (76817) and non-pregnant patient (76830). These studies do not have corresponding limited procedure codes. In these cases, a complete exam would include comments and images for the uterus, endometrium, ovaries, and adnexa. A correlating focused ultrasound exam in the emergency department would seek to identify the location of the pregnancy, presence of an ovarian cyst or fetal heart activity. In this case, the modifier (-52) would be added to indicate reduced service and to demonstrate the study is less than complete when a CPT® code for a limited study is not available (e.g. 76817-26,52).

Question 5: Do the ultrasound images need to be saved and, if so, for how long? Do they have to be saved in the chart or can they be somewhere else like the cloud?

Image retention is important from a reimbursement and medicolegal perspective. While there are no formal guidelines on the location of the images (e.g., cloud based, hard drive, or otherwise), CPT® does require that images from the exam be stored and retained. The number of images and the length of storage time should be discussed with your medical records department.

Question 6: Could both an emergency physician and a radiologist each do their own ultrasound exam and bill for it on the same patient?

In some cases, the answer is yes. But the most important factor is the medical necessity of the exams. If an emergency physician does a limited ultrasound, and either has an inconclusive result or identifies a reason for an additional study in the same anatomical region, there may be a medical necessity for a complete exam to be performed by another clinician (e.g., radiologist). However, there may still be payor specific policies that lead to a denied claim on the second complete study and variation does exist. If you repeated multiple limited exams on the same patient, such as a FAST, you need to demonstrate the medical necessity of those repeated exams. CPT® modifier -76 is added for repeat procedure by the same provider during the same encounter (e.g. 93308-26, 76). Modifier -77 is added for a repeat procedure by a different physician during the same encounter.

Question 7: Is there a difference for billing ultrasound guided procedures?

Ultrasound has significantly improved our abilities as emergency physicians to safely and accurately perform procedures. The most common examples of ultrasound assisted procedures in the ED are ultrasound guidance for vascular access (76937, -26). Compared to the exams mentioned previously, this study uses ultrasound dynamically and it may not be safe to capture an image while the vessel is cannulated. In this case, a pre and post procedure image is sufficient to demonstrate the dynamic nature of the exam. The following exams require static images, where ultrasound is used to landmark the location for entry: ultrasound guidance for needle placement prior to abscess drainage (cutaneous, peritonsillar), lumbar puncture, central line placement. CPT® also provides code options with and without ultrasound guidance for several procedures.

Examples include arthrocentesis (20600, 20604-20606, 20610 - 20611), thoracentesis (32554, 32555) and paracentesis (49082, 49083).

Question 8: What is the value of the commonly performed ultrasounds in the ED?

RVUs based on the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS) eff 4/1/19

If any readers have further questions on billing or suggestions for administrative corner topics, please email us at EUS@aaem.org.

Ultrasound Saves

Chest Pain Conundrum - Bedside Ultrasound Diagnoses a Complex Case of Undifferentiated Chest Pain

Sam Ayala, MD; Uta Guo, MD; and Gerardo Chiricolo, MD

Abstract

Bedside ultrasound quickly leads to discovering dangerous pathologies in unclear patient scenarios. A 33-year-old man with a past medical history of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), presents to the emergency department (ED) with chest pain a day after thoracic trauma and illicit intravenous drug usage. Further morbidity and mortality is averted with the rapid use of cardiac ultrasound to quickly identify a life-threatening diagnosis.

Introduction

The exponential use of ultrasound has allowed it to become an indispensable first-line test for immediate evaluation of symptomatic patients with chest pain. In the practice of emergency medicine, integration of point of care ultrasound (POCUS) has led it to become a fundamental tool to expedite diagnostic evaluation and initiate emergent treatment and triage decisions.1 Bedside ultrasonography, especially echocardiography, is a way in which clinicians can quickly sort through puzzling, and potentially dangerous diagnostic dilemmas. By assessing cardiac function, chamber size, presence of pericardial effusion, and volume status, cardiac pathology can be appropriately investigated.

Case Report

A thirty-three-year-old man with a past medical history of HIV(no known history of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) on anti-retroviral therapy (recent viral load of 21 and a CD4 white blood cell count of 836), presented to ED with acute onset of dyspnea and chest pain. He reports that one day prior to arrival, he attended a “swing” dance club and admitted to alcohol ingestion and cocaine use by injection. While he was dancing, he accidently let go of his dance partner and his back collided into a wall. Two hours later, he began to develop pleuritic chest pain that had worsened by the next morning. His chest pain was left-sided and was described as sharp and radiating to his left flank. He also had a similar pain of lesser intensity six days prior that was associated with fever and myalgias. However, this had resolved in less than one day with bed rest.

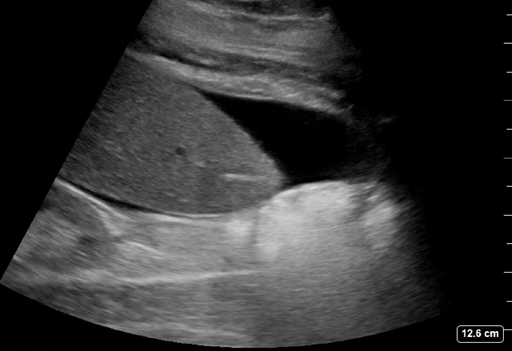

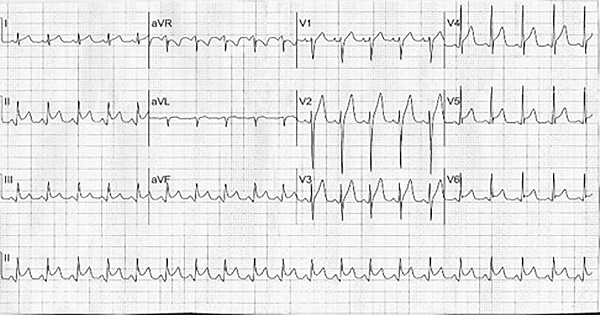

His unrelenting pain prompted him to go to the ED. Initial presenting vital signs were: blood pressure: 136/96, heart rate: 130, respiratory rate: 30 breaths per minute, temperature: 101.1 degrees Fahrenheit, oxygen pulse oximetry: 100% on room air. An initial triage ECG was also performed which showed diffuse, dramatic ST elevations throughout (Figure 1). Subsequently, the patient suffered hemodynamic decompensation soon after arrival with persistent and worsening tachycardia, and a steadily falling blood pressure to 96/60.

Figure 1: Initial triage ECG showing diffuse, dramatic ST elevations throughout all leads.

This case presents a chest pain conundrum, with a wide differential including thoracic trauma, infectious etiology, acute coronary syndrome, and cocaine cardiovascular drug toxicity. His acute presentation of tachycardia, hypotension, and an abnormal ECG prompted a swift investigation into the cause of his worrisome illness with POCUS. In the ED trauma bay, bedside ultrasound showed a small-moderate sized pericardial effusion with possible tamponade physiology. Confirmation by emergent consultative echocardiography indeed showed early sonographic findings of tamponade physiology with right atrial collapse (RAITI- Right Atrial Inverse Time Index). (Figure 2). The decision to delay an emergent pericardiocentesis was made due to the patient’s positive response and improvement with intravenous fluid resuscitation.

Figure 2: Pericardial effusion with possible tamponade physiology (Solid white arrows).

In addition to normal saline intravenous fluids administration, the patient also received acetaminophen for fever treatment, and vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam antibiotics were given to treat infectious etiologies. Further workup with a chest X-ray and a chest computed tomography scan also revealed the patient to have bilateral pneumonia and pleural effusions. Three days post admission a pericardial window with a drain, and a left sided chest tube (for the pleural effusion) were placed. Microbiology culture samples from both areas grew out MRSA (methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus).

The patient’s thirty-seven day hospital stay was complicated by an additional chest tube having to be placed for an enlarging right side pleural effusion, acute tubular necrosis due to vancomycin therapy, sepsis, and constrictive pericarditis after his pericardial window placement. He was discharged home in good condition with a PICC line and continued antibiotic treatment.

Discussion

The diagnosis of cardiac tamponade was originally described by Dr. Claude Beck (1935) as the clinical triad of muffled heart sounds, jugular venous distention, and hypotension.2 However, patients with symptomatic pericardial effusion may not display these classic findings with their clinical scenario. Even though the patient’s history and presentation made the differential diagnoses unclear and he did not present with overt cardiac tamponade, the key to urgent diagnosis and treatment was the use of POCUS. Furthermore, despite not performing an emergency pericardiocentesis, ultrasound could have served an additional purpose of sonography-guided pericardial fluid drainage. In fact, dynamic ultrasound use while draining a pericardial effusion is becoming the standard of care for assisting in this procedure.3

Conclusion

In this fascinating case of chest pain in a young HIV positive patient, POCUS provided an immediate time-critical diagnosis of early cardiac tamponade. In only minutes, bedside ultrasound helped prevent further morbidity and potential mortality. Truthfully, rapid emergency room based ultrasounds have become essential to the everyday practice of emergency medicine.

References

- Labovitz, A, Noble, V, Bierig, M, et al. Focused Cardiac Ultrasound in the Emergent Setting. J Amer Soc of Echo. 2010;23(12):1225-30.

- Goodman, A, Goodman, Adam, Perera, P, et al. The role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. J of Emer, Trauma, and Shock. 2012;5(1):72-75.

- Montandon, M, Wake, R, Raimon, S, et al. Pericardial effusion complicated by tamponade: A case report. So Sudan Med Jour. 2012:5(4).

From Journal to Practice

POCUS and Your Next Cardiac Arrest: A Case Scenario Application of the Lalande et al. Review Article

Samantha King, MD and Ahmed Al Hazmi, MD

Scene

A city medic unit is en route to your emergency department with a 56-year-old man who was found lying in his bed, unresponsive, by family members. At the scene, the first responders could not find a pulse, so they started CPR. Their assessment revealed no evidence of trauma. Cardiac monitoring showed an initial rhythm of asystole. They establish intravenous access via an 18-gauge catheter placed in the left antecubital fossa. They intubate the patient and confirm correct placement of the tube with end tidal CO2 color change and auscultation. CPR is in progress and the patient has received two rounds of epinephrine. The unit will arrive at your door in 5 minutes.

You begin to prepare for your patient’s arrival. You assign roles for the various tasks that will need to be performed, and you gather your equipment: airway tools that can verify correct tube position, a cardiac monitor and defibrillation equipment, IV equipment, and central venous and arterial access setups, all at the bedside. You are ready. But is there something else that you could bring? Why, yes! Your handy ultrasound machine! Every month, you hear of new uses for ultrasound in clinical practice. How can it help you in non-traumatic cardiac arrest?

Literature Dive

In March 2019, Lalande and associates performed a meta-analysis appraising the use of ultrasound in atraumatic, non-shockable cardiac arrest as a reliable predictor of certain outcomes. This meta-analysis reviewed 10 studies of 1,485 patients with initial rhythms of asystole or pulseless electrical activity (PEA) in non-traumatic arrest, who were evaluated for cardiac activity with point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). Outcomes (return of spontaneous circulation [ROSC], survival to hospital admission, and survival to hospital discharge) were evaluated in patients with and without cardiac activity on cardiac POCUS. The investigators found that cardiac activity was associated with an increased likelihood of three outcomes, with a pooled sensitivity of 59.9% and specificity of 91.5%. On subgroup analysis, the sensitivity for asystole was only 24.7% but the sensitivity for PEA was 77.0%. The presence of cardiac activity was also associated with survival to hospital admission and survival to hospital discharge. Notably, this meta-analysis found more heterogeneity in the literature than reported in previous reviews.

Application to Case

The ambulance arrives, and the patient is wheeled into the resuscitation bay. Your prehospital care colleagues give their report while CPR continues on the gurney. Before the patient is transferred to the stretcher, you check for a pulse but don’t find one. CPR continues! You and your team do your best to resuscitate this patient. Pulse check! You still are unable to feel a pulse, but the cardiac monitor shows narrow complex tachycardia. Now is the time to use your ultrasonography skills! The screen shows disorganized cardiac activity with some valvular movement. You continue the resuscitation with high quality compressions, adequate ventilation, and resuscitative medications. After four additional cycles of CPR, ROSC is achieved. The nurse tells you that she feels a strong pulse. POCUS now shows organized hyperdynamic cardiac activity. Subsequent workup reveals no clear identifiable source for the arrest. You start cooling the patient and ultimately hand him off to your colleague in the critical care unit for further resuscitative care. After a long hospital stay, he is discharged to a rehabilitation facility.

POCUS in Perspective

What if you had not seen any evidence of cardiac activity with POCUS? Lalande’s literature review and analysis tells us that a fair proportion of patients who do not have cardiac activity evident on POCUS will still achieve ROSC. So, although the use of POCUS can help you predict patient outcomes and support your resuscitation decisions, we have to remember that POCUS is just another diagnostic tool. Seeing cardiac activity on POCUS is one of many factors that should influence the decision to continue or cease resuscitation. At this time, POCUS should not be the sole predictor in decision making. Rather, in choosing your next steps, it should be used in combination with other factors such as age, length of code time, comorbid conditions, and other findings on POCUS, such as pericardial effusion or right atrial thrombus. For example, if a patient came in pulseless and without signs of trauma, you would have initiated resuscitation but, without seeing a clearly reversible cause of the arrest and with no evidence of cardiac activity, it is likely that you would soon halt the resuscitative attempts. However, if POCUS shows you a large clot swirling around in the right atrium and unorganized cardiac activity, you have the option of reaching for a thrombolytic and continuing the resuscitation.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Linda J. Kesselring, MS ELS, for her copyediting.

Reference

Lalande E, Burwash-Brennan T, Burns K, Atkinson P, Lambert M, Jarman B, Lamprecht H, Banerjee A, Woo MY. Is point-of-care ultrasound a reliable predictor of outcome during atraumatic, non-shockable cardiac arrest? A systematic review and meta-analysis from the SHoC Investigators. Resuscitation 2019 Apr 9 [Epub ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.03.027

Letter to the Editors

What stood out to you from this issue of the POCUS Report? Have a question, idea, or opinion? Alexis Salerno, MD and Melissa Myers, MD FAAEM welcome your comments and suggestions. Submit a letter to the editor and continue the conversation!

Get Involved!

We encourage original submissions to this e-newsletter and to our recurring section in Common Sense. Please contact us with any questions at EUS@aaem.org.