Volume 1 - Issue 3

Summer 2018

Welcome from EUS-AAEM

The Emergency Ultrasound Section of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine (EUS-AAEM) was founded to foster the professional development of its members and to educate them regarding point-of-care ultrasound. This group will serve as a venue for collaboration among medical students, residents and practitioners who are interested in point-of-care ultrasound. The purpose of our group is to augment the knowledge and expertise of all emergency medicine specialists and to advocate for patient safety and quality care by endorsing bedside ultrasound. Membership is not limited to fellowship trained physicians. All emergency medicine practitioners passionate about ultrasound are welcome to join and participate.

We are proud to publish our e-newsletter with original contributions from many of our members. We encourage all members to submit for future additions.Topics include but are not limited to educational, community focus, interesting cases, resident and student section, and adventures abroad.

In this Issue:

-

Board of Directors

-

Back to Basics

-

Ultrasound Highlights

-

Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Fellowships and EMS will Join Toxicology in the EM Subspecialty Match Starting this Fall!

-

Case Report Challenge - Without Ultrasound, You’re SCREWED

-

Ultrasound Guided Procedures

-

Case Report Challenge - Emergency Bedside Ultrasound in Respiratory Distress

-

Membership

Board of Directors

The Emergency Ultrasound Section of AAEM (EUS-AAEM) is proud to announce the new 2018-2019 board of directors.

President

Mark Magee, MD

President-Elect

Eric Chin, MD FAAEM

Secretary/Treasurer

Michael Gottlieb, MD RDMS FAAEM

Directors

Jordan R. Chanler-Berat, MD FAAEM

Melissa Myers, MD FAAEM

Ana Maria Navio Serrano, MD PhD

Allison Zanaboni, MD

RSA Representative

Ben Grugan

In addition to the elected positions above, the following board member will continue in their respective positions.

Immediate Past President

Ryan Gibbons, MD FAAEM

Back to Basics

The utility of two-point compression ultrasonography for detection of a lower extremity deep venous thrombosis in the emergency department.

Norah Kairys, MD

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) cause a great deal of patient morbidity and mortality. For this reason, rapid and accurate detection of this clinical entity is a critical component of the workup of any patient presenting with isolated unilateral lower extremity swelling. In 2006, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) released a guideline recommending the use of emergency bedside ultrasonography to evaluate for a lower extremity DVT.

Whole-leg duplex ultrasonography performed by a radiologist or vascular technician has become an accepted modality to screen for deep venous thrombosis with a reported sensitivity of 91-96% and a specificity of 98-100%.1 For many institutions, this has replaced the use of ascending venography and is now the standard of care in diagnosing a lower extremity DVT. Color flow artifacts and doppler methods can be used to further enhance small vessel visualization.

The problem is, as with most radiologist-dependent ultrasonography, these scans require top-quality ultrasound equipment and experienced operators; which often means they are unobtainable during off-hours. Two-point compression ultrasonography has emerged as an alternative screening modality to evaluate for a lower extremity DVT at the bedside in the emergency department, and this study can be performed by any adequately trained physician.

In two-point ultrasonography, compression is applied to the common femoral vein at the groin and to the popliteal vein at the popliteal fossa.2 Vein incompressibility is considered diagnostic of a deep venous thrombosis. This study is simple, with studies showing that the skill can be proficiently learned in less than two hours, reproducible, and can be performed by virtually all ultrasound trained clinicians.1

In a cross-sectional study by Akhtar Abbasi, et al. (2013), 50 patients with leg swelling and clinical concern for a deep venous thrombosis had a radiology resident preformed two-point compression ultrasound followed by immediate whole-leg duplex ultrasonographic evaluation within 3 hours by a radiologist.1 For this study, pregnant women, patients less than 18, and all patients with a history of a venous thromboembolism were excluded.1 Among the 37 patients who had a positive two-point ultrasound, 74.1% had a confirmed deep venous thrombosis on whole-leg duplex.1 However, among the 13 negative two-point ultrasounds, only 1 (2%) had a confirmed deep venous thrombosis on whole-leg venous duplex, and this one false negative case was found to have an isolated calf vein thrombosis.1 The calculated sensitivity was 97%, specificity 80%, positive predictive value 92% and negative predictive value 92.3%.1

In a prospective, randomized, multicenter study of 2,465 patients with clinically suspected DVT by Bernardi, et al. (2008), patients received either a two-point or whole-leg ultrasonography.3 If the patient was found to have a negative two-point ultrasound they received D-dimer testing.3 Those with positive D-dimer results were sent home without anticoagulation but returned in one week for a repeat two-point ultrasonography.3 Symptomatic venous thromboembolism was found in 7 of the 801 patients who received the two-point protocol versus 9 of the 763 patients in the whole-leg group. 3 At three-month follow-up, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups. 3 Because the long-term outcome of these two groups was found to be equivocal, the authors argue that the need for rapid detection and treatment an isolated calf deep venous thrombosis may not be medically warranted.3

A study by Utter, et al. (2016), investigated the necessity of detection and treatment of isolated calf vein DVT.4 Of the 384 patients found to have an isolated calf DVT, physicians administered therapeutic anticoagulation to 243.4 A proximal vein thrombosis occurred in 7 patients who were not on anticoagulation (controls) and 4 patients that were on anticoagulation.4 A pulmonary embolism occurred in 6 controls versus 4 anticoagulation recipients. Overall, rates of an isolated calf DVT progressing into a proximal vein DVT or a PE were very low.4 Therapeutic anticoagulation was associated with a statistically significant reduction in DVT and PE, but was also found to have an increased risk of bleeding.4 The clinical benefit of treating these isolated calf DVTs in light of the increased bleeding risk remains unclear.4

As a response to the 2012 Guidelines for Anticoagulation Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis published in Chest, Bates, et al., suggest that the pretest probability of DVT should be used to guide the necessary diagnostic process for a first lower extremity DVT.5-7 They recommend initial testing with a D-dimer or ultrasound of the proximal veins (two-point) over no diagnostic testing, venography, or whole-leg ultrasound for patients with a low pretest probability of DVT.5 For patients with a moderate pretest probability, they recommend initial testing with a highly sensitive D-dimer, proximal (two-point) compression ultrasound, or whole-leg ultrasound.5 Lastly, for patients with a high pretest probability, they recommend going straight to proximal (two-point) compression or whole-leg ultrasound.5

Overall, it is clear that two-point compression ultrasound is an accurate and rapid method of diagnosing proximal deep venous thrombosis in patients presenting to the emergency department with isolated leg swelling. Until further studies are conducted to investigate the risk and benefits of treating isolated calf vein DVT, the standard of care should be that if a patient is not found to have a proximal DVT on two-point ultrasonography they should receive D-dimer testing and/or repeat two-point ultrasonography in one week. If a patient opts for D-dimer testing and it is positive, they too will require repeat two-point ultrasonography in one week to exclude the possibility of a propagating calf thrombosis. However, whole-leg ultrasonography is not necessary in the evaluation of patients presenting to the emergency department with isolated lower extremity swelling.

References

-

Abbasi FA, Naeem S, Anwar A, Faisal M, Umar L. Two-point compression ultrasonography for lower extremity deep venous thrombosis in comparison to whole-leg duplex ultrasonography. JRMC. 2017;17:57-59.

-

Adhikari S, Zeger W, Thom C, Fields JM. Isolated deep venous thrombosis: Implications for 2-point compression ultrasonography of the lower extremity. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;66(3):262-266. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.10.032 [doi].

-

Bernardi E, Camporese G, Buller HR, et al. Serial 2-point ultrasonography plus D-dimer vs whole-leg color-coded doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected symptomatic deep vein thrombosis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1653-1659. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1653 [doi].

-

Utter GH, Dhillon TS, Salcedo ES, et al. Therapeutic anticoagulation for isolated calf deep vein thrombosis. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(9):e161770. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.1770 [doi].

-

Bates SM, Jaeschke R, Stevens SM, et al. Diagnosis of DVT: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e351S-e418S. doi: S0012-3692(12)60128-7 [pii].

-

Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, Gutterman DD, Schuunemann HJ, American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):7S-47S. doi: S0012-3692(12)60114-7 [pii].

-

Pruthi RK. Review of the american college of chest physicians 2012 guidelines for anticoagulation therapy and prevention of thrombosis. Semin Hematol. 2013;50(3):251-258. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.06.005 [doi].

Ultrasound Highlights

You Gotta Have Heart - James F. Fair, III, MD

Focused echocardiography is a fun, enriching pursuit for the emergency physician that will continually improve the way you take care of your patients.

Login to your AAEM account to watch this video.

Upper Extremity Blocks You Can Do Tomorrow - Arun Nagdev, MD

Anesthesia for upper extremity injuries can be very challenging. Learning a simplified method to provide analgesia in burns, fractures dislocations and amputations is an important skill for every emergency physician.

Login to your AAEM account to watch this video.

Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Fellowships and EMS Will Join Toxicology in the EM Subspecialty Match starting this Fall!

Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Fellowships will join EMS and Toxicology in the EM Subspecialty Match starting this Fall.

Dr. Jeremy Boyd @geek_md, Ultrasound Fellowship Director and Assistant Program Director at Vanderbilt University Emergency Medicine program in Nashville, TN, sat down with aspiring Emergency Ultrasound Fellow Dr. Neha Bhatnagar @nbhatnagar_md, a current PGY-2 at the University of Tennessee EM residency, to discuss the upcoming Emergency Ultrasound Match process.

NB: “My first question about Ultrasound fellowships going to the Match system is why?”

JB: This year is the first year that Emergency Ultrasound, or Clinical Ultrasound, is going to be in the Match. We’re doing that for a number of reasons: tracking, logistics, professionalism, etc. The application process has become a bit complicated and difficult, presenting multiple challenges to both applicants and fellowship directors. The Match system is a very complex algorithm that tries to optimize this puzzle of matching applicants where they want to go and directors with who they want to have, and it couples that with a legal commitment. Ultrasound and EMS are going to be in the EM Subspecialty Match this year, joining Toxicology, which has already been using this system for a while now.

NB: “What are the deadlines applicants need to know?”

JB: The deadlines for all EM Fellowships -- Ultrasound, EMS, and Toxicology -- are all the same, and you can find them on the NRMP website under EM Subspecialty Match.

- August 22 at 12:00pm EST - EM Subspecialty Match opens

- September 26 at 12:00pm EST - Ranking opens

- October 31 at 9:00pm EST - Rank Order List (ROL) Deadline for Submission and Certification

- November 14 at 12:00pm EST - Match Day! Offers will be sent via email

So the most important deadline for applicants to remember is to submit and certify your ROL by 9:00pm EST on Halloween!

NB: “What is the process for applying to Ultrasound Fellowships?”

JB: Interested applicants can register and apply through the Emergency Ultrasound (EUS) Fellowships website, out of which the The Society of Clinical Ultrasound Fellowships (SCUF) has grown. There they can upload their CV, personal statement, and Letters of Recommendation. Then they can choose which programs they want to see their application. It is important to note that the EUS Fellowships website will soon be going through an upgrade.

NB: “What is the interview process like?”

JB: This year, given the deadlines, interviews will all be shifted a little earlier into September and October. Interviews commonly take place at the fall national conferences, such as the ACEP Scientific Assembly.

NB: “Which Ultrasound Fellowships are participating in the match? How can we find out more information about the programs?”

JB: Every fellowship that is part of SCUF will be participating in the Match through the EUS fellowships website, which has more comprehensive details about each program’s goals and focuses. Every program has their own unique strengths and format, whether it is operations, education, research, or mentoring.

NB: “Will applicants be able to obtain a fellowship outside of the Match through more informal interviewing? And is there a SOAP or ‘scramble’ with the fellowship Match?”

JB: All applicants who want to do a fellowship in Ultrasound are going to need to go through the Match. There will no longer be informal fellowship offers outside of the Match. And there is no formal SOAP. If a program does not fill after the Match, then the EUS Fellowships website will have that information and be able to provide that to interested applicants who can then contact those programs.

NB: “What are the estimated costs that applicants can expect?”

JB: The NRMP and EUS Fellowship websites both list their registration fees. The total estimated cost for an applicant applying to eight sites for Ultrasound Fellowship will be $110, which is certainly a lot less than it was for residency!

NB: “How does couple’s matching into EM Fellowships work?”

JB: Something that is new this year is that if there are two applicants, each interested in one of the three EM subspecialties in the Match, and they both want to go to the same site, they can actually couples match together! For example an Ultrasound applicant can couple’s match with an EMS applicant for a small additional fee, and the Match will automatically incorporate that into the algorithm.

NB: “How can applicants show their interest and improved their application?”

JB: The biggest thing really comes down to sound clinical ability. You can be great at obtaining images on ultrasound, but if you do not have great clinical acumen overall, you are not going to be as strong of an applicant as you could be. There is an interview on the Academic Life in EM (ALiEM) website, in which Dr. Chris Fox, who is the Ultrasound Fellowship Director at UC Irvine, and I are interviewed regarding Ultrasound Fellowships, and I would recommend applicants watch that video. Strong interest or experience in Ultrasound helps, but you certainly do not have to show expertise in Ultrasound in order to get a fellowship position. Research and publications are nice, but also are not critical. Do something in residency to show that you will be able to get involved in a research project during your fellowship year, but most programs would still prefer a strong clinician-educator over someone who was churning out papers every day.

NB: “What Ultrasound conferences or events would you recommend interested applicants attend throughout the year?”

JB: Anything with the Ultrasound Sections or Committees of AAEM, SAEM, and ACEP would be great opportunities to get a better sense of what the community is like and how to get involved. SCUF is a unique conference as well, and though it is geared toward fellowship directors and fellows, residents are also welcome there. American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) is an ultrasound conference not just for EM physicians, but also for radiology, cardiology, OBGYN, etc. There are also various private Ultrasound courses that have educational and networking opportunities.

NB: “Do you have to do a fellowship in order to show your expertise in Ultrasound?”

JB: While you do not need a fellowship in order to practice point of care ultrasound clinically, especially now that residencies have incorporated it into their curriculum, anyone who wants to do something more like be an Ultrasound director, educator, or division chief will likely need to have a fellowship. Formalizing and standardizing the fellowship process is our way of providing our own accreditation as Emergency Ultrasound strives for professional recognition as a Designation of Focused Practice (DFP) within EM.

NB: “Do you have anything else to add?”

JB: I know a lot of people have anxiety about the Match left over from the residency process, and that this new process could bring that anxiety back up, but applying to Ultrasound fellowship is very different than applying to residency. Emergency medicine is a small, close-knit community, and the Ultrasound community within it is even smaller. Moving to the Match is going to be a really positive change toward transparency and professionalism.

NB: “Thank you, Dr. Boyd, for taking the time to talk with me about this. There are certainly exciting changes coming in the future of Emergency Ultrasound, and I for one am looking forward to becoming a part of that community!”

JB: Absolutely! I am happy to do it! And thank you too, Neha! I hope this is helpful, and if anyone has any further questions, I again encourage them to use the resources mentioned.

Resources:

- EUS Fellowships Website: http://www.eusfellowships.com/

- NRMP EM Fellowship Match Deadlines: http://www.nrmp.org/fellowships/emergency-medicine-match/

- NRMP Match Fees: http://www.nrmp.org/match-fees/

- AAEM’s Emergency Ultrasound Section (EUS): https://www.aaem.org/get-involved/sections/eus

- ACEP’s Ultrasound Section: https://www.acep.org/how-we-serve/sections/emergency-ultrasound/education-and-training/#sm.0000ik1f6b13t5dqmyf85g7sfi8j2

- SAEM’s Academy of Emergency Ultrasound (AEUS): https://www.saem.org/aeus/get-connected/fellows'-corner

- EMRA Ultrasound Section including the Fellowship guide chapter for Ultrasound: https://www.emra.org/be-involved/committees/ultrasound-committee/

- ALiEM’s EM Fellowship Match Advice: https://www.aliem.com/2015/10/em-fellowship-match-advice-simulation-toxicology-ultrasound/

- American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM): https://www.aium.org/

Case Report Challenge

Without Ultrasound, You’re SCREWED

Michael Chang, MD, PGY-3 at The Brooklyn Hospital Center

It’s a Tuesday morning, you’ve had your first cup of coffee and your shift is going well so far. Suddenly, your nurse wheels in a young man who appears to be in agony. It is not until you see the long grey screw sticking out of the bottom of his running shoe that you realize why he is cringing in pain.

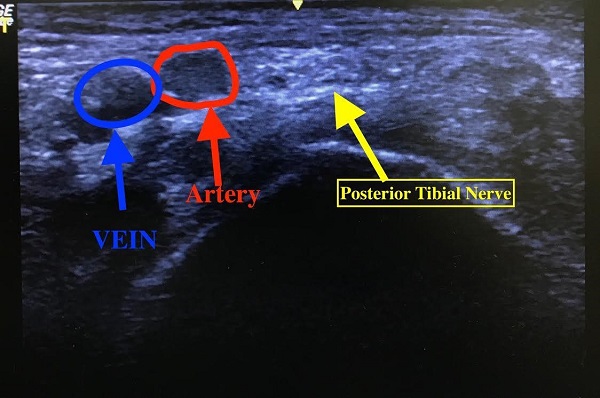

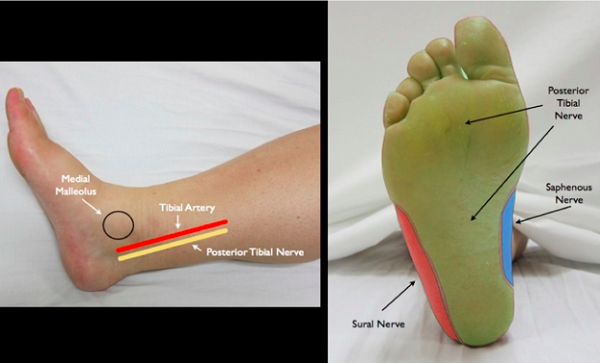

The patient, a young entrepreneur opening up a new nearby restaurant, had stepped firmly onto a construction screw which perfectly impaled itself into the sole of his shoe and into his foot! We were unable to visualize the sole of his foot and any movements of his foot caused extreme discomfort. This made our assessment of the depth and a thorough neurovascular exam impossible. We had to get that sneaker off! Rather than do conscious sedation which would require monitors, nursing, and airway equipment along with its inherent risks, we decided to do a posterior tibial nerve block of his foot recognizing that the posterior tibial nerve supplies the sensory innervation of the sole of the foot (see image below).

This image is copyrighted by Michael Chang, MD and Jordan Chanler-Berat, MD FAAEM. We have been granted to use it for this article.

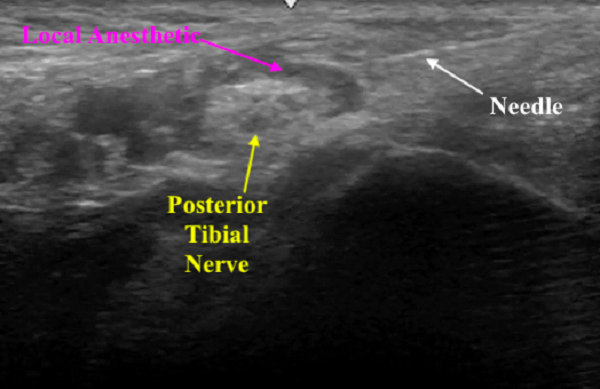

Placing the linear probe slightly posteromedial to the medial malleolus, we were able to visualize the posterior tibial nerve along with its vascular bundle (see the attached image). After prepping the patient in usual sterile fashion, and drawing up approximately 8cc of 0.25% bupivacaine, we used an in-plane technique with the needle carefully directed at the nerve. We were able to visualize the needle tip as it approached the nerve and when the needle was approaching the nerve we were able to hydrodissect the soft tissues around it. About 5 minutes later the patient reported almost complete anesthesia to the sole of his foot.

After anesthesia was achieved we were able to manipulate the patient’s foot and sneaker. We could then safely cut off sneaker which required a lot of pulling and foot manipulation but the patient tolerated this well. The screw was subsequently removed with gentle manual traction after radiographs confirmed no bony involvement and the patient tolerated the procedure well with no complications. He was grateful that we avoided procedural sedation which he was very nervous to receive and we were glad to avoid narcotics. This nerve block is a great option to anesthetize and control pain to a tricky region of the body, the sole of the foot. In our nation’s current opioid epidemic our ED is focused on reducing opioid use when possible and keeping opioid naive patients from exposure to opioids unnecessarily.

This image is copyrighted by Michael Chang, MD and Jordan Chanler-Berat, MD FACEP FAAEM. We have been granted to use it for this article.

This image is copyrighted by Arun Nagdev, MD. We have been granted to use it for this article.

This image is copyrighted by Michael Chang, MD and Jordan Chanler-Berat, MD FACEP FAAEM. We have been granted to use it for this article.

References

- NYSORA (New York School of Regional Anesthesia). Ankle Block Lower Extremity 2013. https://www.nysora.com/ankle-block. Accessed April 10, 2018.

- Highland EM Ultrasound Fueled Pain Management. Ultrasound Guided Posterior Tibial Nerve Block. http://highlandultrasound.com/posterior-tibial-block/. Accessed April 11, 2018.

- Giron-Arango L, Vazquez-Sadder M, Gonzalez-Obregon M, Gamero-Farjado E.Ultrasound-guided Ankle Block: An attractive anesthetic technique for foot surgery. Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology. 2015, 43(4): 283-289. doi.org/10.1016/j.rcae.2015.07.003

Ultrasound Guided Procedures

Ultrasound Guided Subclavian Lines: Infraclavicular Approach

MAJ Melissa Myers, MD FAAEM and LTC Eric Chin, MD FAAEM

Emergency Medicine Ultrasound Fellowship, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Antonio Military Medical Center

Case Scenario

It’s Friday night in a busy emergency department. EMS calls and says they’re bringing a patient from a motor vehicle collision. She’s hypotensive and they’ve placed an IO but are having trouble getting peripheral intravascular access. On arrival, she remains hypotensive and you start a blood transfusion but need more access. You notice track marks on both arms and anticipate significant difficulty with peripheral access. You set up for a subclavian central line but are concerned about possible complications such as non-compressible arterial puncture or pneumothorax.

Difficulty with peripheral access is a common scenario in emergency departments nationwide. The subclavian central line has seen decreased use in recent years with the use of ultrasound-guided peripheral access and internal jugular central access seen by many physicians as safer, quicker options. However, in trauma patients with cervical collars, patients with internal jugular thromboses and in certain other situations the subclavian line may be the central venous line of choice. Furthermore, the CDC currently recommends the subclavian line in adults to decrease rates of central line infection.1 Using ultrasound guidance when placing a subclavian central line can improve the success rate while decreasing time to vascular access and complications such as arterial puncture and pneumothorax.2

Physicians are often concerned that the subclavian vein will be difficult to visualize due to the overlying first rib, however, the technique described below allows for a clear view of the subclavian artery and vein without interference from the first rib.

Infraclavicular Ultrasound Guided Central Access

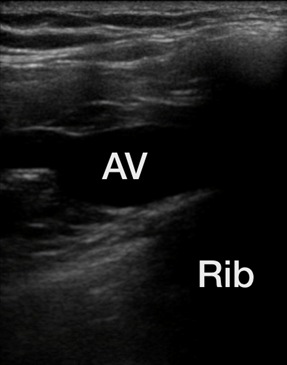

- Place a high frequency (linear) ultrasound probe in the mid-clavicular line approximately 1/3 of the distance from the acromioclavicular joint to the sternum with the probe indicator pointed at the patient’s head. This will give you a transverse (short) view of the subclavian artery as seen in Figure 1.

- Move the indicator laterally, until the rib is no longer obscuring any part of the vascular structures.

- Turn the indicator until the probe is parallel to and directly underneath the first rib. You will see the axillary vein in the long axis as seen in Figure 2. Note that in this figure you can see take-off of the cephalic vein.

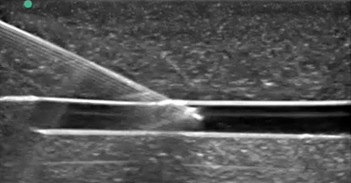

- From this position, you will cannulate the vein in the long access using the same technique as peripheral access as seen in Figure 3 (a model has been used for the demonstration.)

One potential pitfall with this technique is the accidental visualization of the axillary artery instead of the axillary vein. If you are unable to compress the vessels, color Doppler or spectral Doppler can be used to differentiate between the two vessels. Complications such as penetration of the posterior wall of the vein are not eliminated with the use of ultrasound, however use of the long axis view during catheter insertion may decrease the chances of this complication.4 Finally, as with many other procedures, ultrasound may increase success rates in physicians with less experience.5

Case Conclusion

Using ultrasound guidance, you place a subclavian central line without complications and complete resuscitation of the patient. She is taken to the operating room where a splenic rupture is diagnosed and treated and ultimately recovers.

Figure 1. Subclavian Vein in the Tranverse (Short) Axis

This image is copyrighted by Melissa Myers, MD. We have been granted to use it for this article.

Figure 2. Axillary Vein in the Long Axis with Take-Off of the Cephalic Vein

This image is copyrighted by Melissa Myers, MD. We have been granted to use it for this article.

Figure 3. Long Axis Vessel Cannulation

This image is copyrighted by Melissa Myers, MD. We have been granted to use it for this article.

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/bsi/recommendations.html

- Fragou, M., Gravvanis, A., Dimitriou, V., Papalois, A., Kouraklis, G., Karabinis, A., ... & Labropoulos, N. (2011). Real-time ultrasound-guided subclavian vein cannulation versus the landmark method in critical care patients: a prospective randomized study. Critical Care Medicine, 39(7), 1607-1612.

- Ma, O. J., Mateer, J. R., & Blavias, M. (2008). Emergency Ultrasound. New York.

- Blaivas, M., & Adhikari, S. (2009). An unseen danger: frequency of posterior vessel wall penetration by needles during attempts to place internal jugular vein central catheters using ultrasound guidance. Critical Care Medicine, 37(8), 2345-2349.

- Gualtieri, E., Deppe, S. A., Sipperly, M. E., & Thompson, D. R. (1995). Subclavian venous catheterization: greater success rate for less experienced operators using ultrasound guidance. Critical Care Medicine, 23(4), 692-697.

Case Report Challenge

Emergency Bedside Ultrasound in Respiratory Distress

Jessica Jackson, MD, PGY-2

Department of Emergency Medicine, Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia PA

A 68-year-old female presented to the emergency department by EMS in respiratory distress. She was placed on CPAP in the field due to severe respiratory distress with increased work of breathing and tripod positioning. Two family members were present who confirmed EMS’s account that the patient has a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and that this presentation is typical of her COPD exacerbations, for which she has frequent emergency department visits and admissions. She also has a past medical history of congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and rheumatoid arthritis. The patient complained of two days of increasing shortness of breath and chest tightness, but further history and review of systems was limited by her respiratory status.

Her vital signs on arrival were blood pressure 106/65mmHg, heart rate 130 beats per minute, respirations 32 breaths per minutes, temperature 98.7oF, and oxygen saturation 100% on the non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. Physical exam revealed an obese female with tachypnea, diminished heart and lung sounds, bilateral lower extremity edema, diaphoresis, and cool extremities.

The treating physician performed bedside ultrasound on arrival to assess for other pathology that may be contributing to her presentation. Ultrasound of the lungs showed no effusion or B lines to suggest pulmonary edema. Ultrasound of the heart showed a 2.6cm, circumferential pericardial effusion. Assessment for tamponade physiology was limited due to the patient’s body habitus. A stat consult was made to cardiology whose bedside echocardiogram confirmed the presence of a large circumferential pericardial effusion with right ventricular diastolic collapse.

While preparing the patient for transport to the catheterization lab she became progressively more altered and required intubation. Materials needed for bedside pericardiocentesis were made available. Shortly after intubation the patient went into a PEA arrest. Advanced cardiac life support was initiated and ultrasound guided pericardiocentesis was attempted. A small amount of bloody pericardial fluid was obtained, but did not significantly change the patient’s hemodynamics or the size of the effusion on ultrasound. A bedside medical thoracotomy was then performed which released a large amount of bloody pericardial fluid. Open cardiac massage was initiated and shortly after the patient had return of spontaneous circulation. She lost pulses a number of times over the next hour while being evaluated for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Physicians were unable to maintain a perfusing rhythm despite multiple vasopressors and the patient ultimately expired less than three hours after arrival.

This case provides a dramatic example of the utility of emergency bedside ultrasound in assessing patients with respiratory distress. Patients frequently have multiple comorbid conditions that can each lead to respiratory distress but identifying the correct diagnosis to guide treatment of the current presentation is essential. Regular assessment of patients in respiratory distress with bedside ultrasound can frequently lead to a change in the diagnosis and treatment plan. One study showed that fifty percent of providers changed their leading diagnosis after using ultrasound in the evaluation of dyspneic patients.1 Studies have also shown a high concordance between ultrasound and chest X-ray findings in these patients and a decrease in the time to diagnosis when using ultrasound.2,3 An ultrasound performed to help narrow the differential diagnosis for a patient in respiratory distress should include clips of the bilateral lung bases and apices, as well as the heart. This imaging can reveal a wide range of pathology causing respiratory distress including pneumothorax, pulmonary edema, pleural effusion, heart failure, signs of pulmonary embolism, and pericardial effusion. In the above case, the patient was presented by both EMS and family as a clear COPD exacerbation. By performing bedside ultrasound, physicians were not only able to determine that the patient’s presentation was secondary to tamponade, but were able to mobilize the appropriate resources and consultants within minutes of the patient’s arrival in the emergency department.

References

- Papanagnou D, Secko M, Gullett J, et al. Clinician performed bedside ultrasound in improving diagnostic accuracy in patient presenting to the ED with acute dyspnea. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017; 18(3): 382-389.

- Zanobetti M, Poggioni C, Pini R. Can chest ultrasonography replace standard chest radiography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED. Chest. 2011; 139(5): 1140-1147.

- Zanobetti M, Scorpiniti M, Gigli C, et al. Point-of-care Ultrasonography for evaluation of acute dyspnea in the ED. Chest. 2017; 151(6): 1295-1301.

Membership - Join Today!

If your AAEM membership is current, please click here to add the Emergency Ultrasound Section.

If your AAEM/RSA membership is current, please click here to add the Emergency Ultrasound Section.

You can add the Emergency Ultrasound Section when you are renewing or joining AAEM and AAEM/RSA during the application process online!